GOAT Network Research Group

Email: contact@goat.network

Jan 2026 - Version 1.0

Abstract. The BitVM2 protocol is often regarded as one of the most secure bridge frameworks for Bitcoin and its side-systems. However, it still faces challenges in a real-world zkRollup setting and deployment, such as the inability to support arbitrarily sized withdrawals, inconsistent challenge incentives, potential double-spending attacks by operators, and large on-chain data for dispute resolution.

To address these issues (without compromising the 1-of-n honesty assumption), we introduce a trust-minimized settlement protocol—enabling native zkRollups on Bitcoin—called GOAT BitVM2. 1) This includes a method for committing ZK proof public inputs to Bitcoin as part of BitVM2’s optimistic computation, e.g., a commitment to the L2’s sequencer-set configuration. With this, both state transitions and the latest L2 state can be verified by the sequencer set on Bitcoin, resisting potential double-spending attacks by operators. 2) The operator and challenger collateral in the BitVM2 protocol are moved onto L2, with the operator’s reimbursement constrained by a chain based synchronization primitive, in combination with CPFP1, improving the operator’s capital efficiency. 3) By integrating with Atomic Swap, this protocol allows end-users to withdraw from L2 to L1 with arbitrary amounts, and the operator reimburses themselves using L2 state transition proofs.

The subsequent innovation of the BitVM2 architecture, integrating garbled circuits (GC) with designated-verifier (DV) SNARKs, further optimizes performance and reduces on-chain costs. By shifting computations (e.g., the SNARK verifier) off-chain with GC, committing the GC’s inputs and output labels on-chain and revealing the input labels when challenged to compute the output cleartext, the system minimizes its on-chain footprint. The correctness of the GC is guaranteed by zero-knowledge proofs, while the validity of the DV-SNARK’s Structured Reference String (SRS) is ensured via pairing verification for the BN254 curve, and through a combination of the Cut & Choose technique and a random challenge mechanism for the Sect233k1 curve, thereby achieving a balance between on-chain and offchain complexity.

All implementations are publicly available on GitHub at BitVM, BitVM2-node, and bitvm2-gc, facilitating reproducibility and further research.

Keywords: GOAT Network, BitVM2, Garbled Circuits, zkVM, zkRollup, Cross-chain Bridge

BitVM [12] and its evolutions BitVM2 [13], proposed by Robin Linus et al., establish a trust-minimized bridge protocol for Bitcoin [14]. They enable Turing-complete smart contracts and side systems (like zkRollups) through a fraud-proof arbitration mechanism without requiring a hard fork, operating under the 1-of-n honesty assumption2. The protocol leverages pre-signed transactions, one-time signatures, and SNARK proofs to verify off-chain computations on-chain, conceptually similar to Optimistic Rollups in Ethereum [16][2].

Serving as the cryptographic foundation for cross-chain bridges and zkRollups, the original BitVM2 protocol achieves two key breakthroughs: 1) Maintaining Bitcoin’s base layer integrity

without protocol forks under the 1-of-n honesty assumption; 2) Compared to BitVM, BitVM2allows anyone to challenge and slash a faulty Operator with only three on-chain transactions, with a delay of no more than 2-3 weeks, thus enabling a relatively capital-efficient improvement.

However, the BitVM2 protocol continues to grapple with significant on-chain costs and operational inefficiencies. Delbrag [17] (and subsequently BitVM3 [11]) dramatically reduces on-chain costs using garbled circuits (GC) [19]. During setup, a Garbler commits to a SNARK verifier circuit in a Taproot tree and shares it with an Evaluator. If the Garbler submits an invalid SNARK proof, the Evaluator generates a fraud proof using the pre-shared circuit. This approach retains

BitVM2’s trust model while minimizing its on-chain footprint. This is achieved by directly verifying the output label for publicly verifiable garbled circuits.

Representing the verification circuit as a Boolean circuit results in an extremely large circuit size, with the number of gates reaching billions. This massive circuit imposes a significant burden on both off-chain data storage requirements and the computational complexity of proving the correctness of the GC construction. Although algebraic GC circuits offer a way to reduce the circuit scale, current schemes [8] can only support computations over integers and cannot efficiently simulate modulo operation over a large prime. Alpen Labs’ [3] proposed using SNARK schemes with designated

verifiers (DV-SNARK) on the binary curve to reduce the size of the GC circuit in the ZKP verifier, as a sequencer converts Elliptic Curve Pairing to Multiple Scalar Multiplication and greatly reduces the circuit size. For applications requiring different trade-offs, we provide two elliptic curve options: BN254 and Sect233k1. The BN254 curve is pairing-friendly, allowing efficient pairing operations, which enables straightforward verification of the SRS validity, and it is crucial to support more concise and efficient protocol sequences. Alternatively, the Sect233k1 curve is defined over a binary extension field. This characteristic supports constructing significantly smaller GC implementations and reduces the GC size by two orders of magnitude.

In addition to the significant on-chain inefficiencies, use of BitVM2 to build a practical Bitcoin zkRollup faces some critical challenges, listed below.

Operator’s Double-Spending Attack: When the operator gets challenged and reveals the execution trace of the ZK proof’s verifier, and the proof is the commitment of the L2’s state transition, then an Operator could potentially create a valid proof for an incorrect or forked state (e.g., from an L2 fork) and use it to fraudulently withdraw funds, executing a double-spend. How to determine the correct latest state root becomes an issue since we can’t trust the operator to publish the proof’s public input, especially when the L2 has its own decentralized sequencer network.

Inability to Withdraw Arbitrary Amounts: The operator in BitVM2 is able to withdraw from Tapscript in the Peg-in transaction, however it is not possible for every end-user of an L2 to run an operator. Furthermore, the peg-in transaction amount is fixed, hence it is necessary to allow end-users to withdraw arbitrary amounts from L2 to L1.

Misaligned Incentives: BitVM2 lacks a practical incentive mechanism suited for real-world deployment. This could result in serious security vulnerabilities if there are not enough challengers or operators participating in the network. For instance, if no fraud occurs over an extended period, challengers might not receive sufficient rewards to stay motivated and could decide to exit the protocol. An additional concern is that challengers may not receive their rewards. During the crowdfunding process for the Challenge transaction, the original challenger may not be the one who ultimately submits the final Disprove transaction - a Bitcoin miner could front-run the transaction to claim the rewards instead. As a result, the staked funds may not be properly distributed to the honest challenger.

GOAT BitVM2 combines three architectural innovations to overcome these limitations.

Decentralized Sequencer Set Commitment Scheme: This innovation addresses the double-spending attack by securely anchoring the L2 state on Bitcoin. Instead of directly trusting the Operator’s public input, the system commits to the state of a decentralized sequencer set (e.g., their public keys) via a Bitcoin transaction. This committed state x then becomes a verifiable public input3 for the computation f(x, w) = y in the Kickoff process, ensuring the Operator’s proof is based on the canonical L2 state.

Universal Operator Abstraction: To balance risks and incentives, the distinct roles in the system (Operator, Challenger, Committee, Sequencer, and Watchtowers, etc.) are unified into a single Universal Operator role. Participants stake funds and are assigned different roles over time through a rotation mechanism. This ensures that no single entity is permanently burdened with high-cost roles or only profitable ones, leading to a more stable and sustainable economic model.

NIZK based Verifiable Garbled Circuit: Using GCs to improve the optimistic challenge efficiency - instead of verifying Groth16 on Bitcoin, DV-SNARKs can significantly reduce on-chain computation complexity. In such a setting, the L2’s state transition is proven with Ziren4 and the STARK proof is wrapped to the DV-SNARK proof, before the DV-SNARK verifier is proven by Ziren for BitVM2’s dispute resolution.

Combining these innovations, GOAT BitVM2 improves on the theoretical framework of BitVM2, resulting in a pragmatic, efficient, and secure foundation for Bitcoin zkRollups.

A zkRollup is a Layer-2 (L2) scaling solution that executes transactions off-chain while submitting succinct validity proofs to the underlying Layer-1 (L1) blockchain. By leveraging zero-knowledge (ZK) proof systems (e.g., Groth16), zkRollups cryptographically guarantee the correctness of off-chain state transitions without requiring transaction re-execution on L1.

The core architecture of zkRollups is guided by the following two principles:

1. Succinct Verification: All off-chain computation is verified on L1 via succinct ZK proofs, preserving integrity while avoiding redundant execution.

2. Data Availability: Only essential state data (e.g., state differences or compressed transaction data) is published on L1 to ensure data availability.

Fig. 1 illustrates the generic workflow of a zkRollup system. Users deposit assets on L1, which are then represented and transacted on L2. After off-chain execution, the updated L2 state is committed to L1 together with a validity proof, enabling trust-minimized withdrawals back to L1.

Deposit (also referred to as Peg-in within the BitVM2 context): A user deposits assets by locking them on L1 non-custodially. The zkRollup sequencer detects this event, validates the finality of the deposit transaction, and updates the L2 state accordingly—typically by minting equivalent wrapped tokens on L2.

Transaction Execution and State Commitment: A sequencer batches L2 transactions, executes them off-chain, and generates a new L2 state root (e.g., a Merkle root representing the latest state). The sequencer then publishes the raw transaction data (for data availability) and a validity proof (e.g., a zk-SNARK) to the L1 verifier contract. The proof attests to the correctness of the state transition.

Withdrawal: To withdraw assets from L2 to L1, a user submits a burn transaction on L2. The sequencer includes this in the next batch, generating a validity proof for the updated state (which reflects the burned L2 tokens). The user then submits a Merkle proof to the L1 contract, which verifies the validity proof and releases the locked L1 assets.

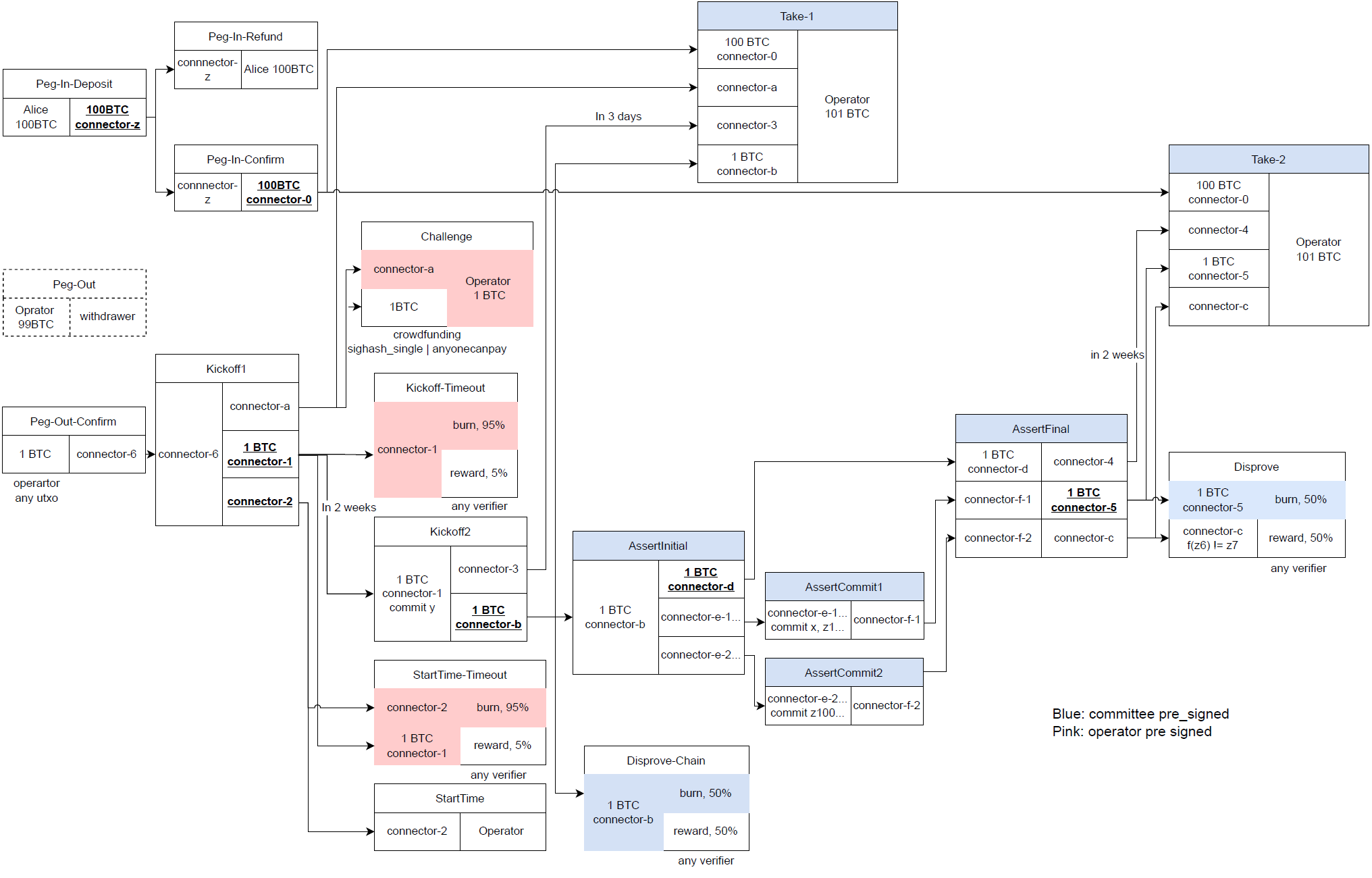

As shown in Fig. 2, BitVM2 uses the presigned Transaction Graph5 to achieve logic persistence, and uses a one-time signature [10] to implement storage persistence. In combination with timelock and Taproot, BitVM2 can be used to implement a trust-minimized bridge protocol between Bitcoin and an L2.

The protocol operation can be condensed into three key phases:

Peg-In-Deposit transaction. The Operator must respond with a Peg-In-Confirm transaction for the user to receive equivalent assets on L2. If the Operator fails to respond, the user can retrieve their BTC using a Peg-In-Refund transaction after a timeout.Kickoff transactions. This starts a dispute period (e.g., two weeks). A Challenger can contest the withdrawal during this time if they detect fraud (e.g., the Operator using an invalid L2 state).Take1 transaction to get reimbursed seamlessly.Take2 transaction.BitVM is one of the promising protocols to build bridges between Bitcoin and side-systems, with its core innovation being a trust-minimized solution achieved through the BitVM smart contract. This solution is based on a key design principle: the security of funds is guaranteed as long as there is at least one honest participant in the system who can detect and challenge malicious behavior. This approach fundamentally eliminates the dependence on centralized authorities or multisig set-ups.

A zkVM (Zero-Knowledge Virtual Machine) is a cryptographic system that enables verifiable computation by generating a ZK proof for arbitrary program executions. It allows developers to write code in high-level programming languages (e.g., Rust, Go) and compile it into instructions compatible with specific Instruction Set Architectures (ISAs). The zkVM executes these instructions, generates a trace of the execution recording register states and memory accesses at each clock cycle, and produces a succinct proof to validate the correctness of the computation. Key components include zkCompiler, Prover and Verifier.

zkCompiler: Compiles high-level code into ISA-specific binaries (e.g. MIPS, RISC-V), generates execution traces, and converts the traces into polynomials for constraint satisfaction checks.

Prover: Commits the polynomials, and generates ZK proofs. Compared to native execution, Zero-knowledge proving is currently slower by 100-1000x. Hardware acceleration, continuation6, and pipelined proving are exploited to reduce computing overhead and latency.

Verifier: A program to verify ZK proofs, run in an L1 smart contract or covenant to share the security of an L1’s consensus and achieve the finality and settlement of an L2’s state transitions.

Ziren [18] is a production-grade zkVM based on the MIPS32r2 instruction set, a stable RISC architecture known for deterministic execution and minimal circuit overhead. Developed by the ZKM7 team, it optimizes zero-knowledge proof generation through efficient zkCompiler, pipelined proof architecture, and a cutting-edge proof system, ensuring high instruction proof efficiency and reduced audit requirements. Ziren demonstrates remarkable performance when accelerated by a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, achieving a computational throughput of more than 4 million Hz. This high-performance capability is particularly evident in its handling of the Poseidon2 hash function, for which it can generate over 300,000 proofs per second.

A Garbled Circuit (GC) is a cryptographic protocol, introduced by Yao [19] in 1986, that enables secure two-party computation. It allows two distrustful parties to jointly compute a function on their private inputs without revealing those inputs to each other. The core idea is to encode the function as a Boolean circuit (composed of gates like AND, OR, XOR etc.). One party, the Garbler, encrypts or ”garbles” the truth table of each gate, turning meaningful binary values (0/1) into random-looking labels. The other party, the Evaluator, then obliviously evaluates this encrypted circuit using these labels - through a process like Oblivious Transfer (OT) to obtain the labels corresponding to their own inputs - and learns only the final output without gaining any information about intermediate values or the Garbler’s inputs. This approach supports arbitrary functions with a constant round of interaction. While early GCs had high communication costs, key optimizations like free-XOR [9] (making XOR gates virtually free in terms of cost) and point-and-permute (which allows the Evaluator to decrypt only one entry per garbled table) have significantly improved efficiency.

GC is compatible with optimistic verification computation on Bitcoin as introduced in Delbrag [17]. In a GC protocol, the protocol proceeds in three rounds: garble, authenticate, and evaluate - and is carried out entirely off-chain.

For a SNARK verifier circuit, if the protocol is secure, then the Evaluator should learn the output 1-label if and only if the Garbler authenticated a valid proof input. So, the output 0-label constitutes a fraud proof. Given an authentication mechanism that is compatible with GC and verifiable on chain, we can use this fraud proof to slash on-chain.

GOAT BitVM2 adopts the Poseidon2 hash function \(H(·)\) as the cryptographic primitive for garbled circuit (GC) construction, and follows the free-XOR optimization together with the secret-free garbling technique introduced in [5]. The garbler constructs the GC according to the following procedure.

Global Setup. The garbler samples a global offset \(r \in \{0, 1\}^\lambda\). For every wire \(w\), the associated wire labels \(w^0\) (encoding bit 0) and \(w^1\) (encoding bit 1) satisfy

\[w^1 = w^0 \oplus r\]

Input Wire Label Generation. For each input wire w, the garbler samples \(w^0\{0, 1\}^\lambda\) uniformly at random and derives \(w^1 = w^0 \oplus r\).

Gate Garbling. Let a and b denote input wires, o the output wire, and gid the unique identifier of the gate.

\[w_o^0 = w_a^0 \oplus w_b^0\]

\[w_o^0 = w_a^1\]

\[w_o^0 = H(w_a^0, \text{gid})\]

and generates a single ciphertext

\[c = H(w_a^1, \text{gid}) \oplus w_o^1 \oplus w_b^1\]

\[w_o^0 = H(w_a^1, \text{gid}) \oplus r\]

and generates a single ciphertext

\[c = H(w_a^1, \text{gid}) \oplus H(w_a^0, \text{gid}) \oplus w_b^1\]

For every output wire o, the 1-label is derived as

\[w_o^1 = w_o^0 \oplus r\]

Gate Evaluation. Given garbled input labels \(w_a^x\) and \(w_b^y\), where \(x, y \in \{0, 1\}\) are the encoded bits (note that the NOT gate requires only \(w_a^x\)), the evaluator computes the output label \(w_o\) as follows.

\[w_o = w_a^x \oplus w_b^y\]

\[w_o = w_a^x\]

DV-SNARK is an optimized variant of SNARK designed to address the high on-chain costs and computational overhead associated with traditional SNARK verification circuits. It achieves this by replacing expensive cryptographic operations with more efficient alternatives, making it particularly suitable for blockchain applications like Bitcoin L2 solutions, where minimizing the on-chain script is critical.

Traditional SNARKs (e.g., Groth16 [7]) rely on elliptic curve pairings for verification, which require complex operations in large prime fields. These operations must be encoded as binary circuits when integrated with GC, leading to massive circuit sizes (billions of gates) and prohibitive off-chain communication cost.

DV-SNARK uses a designated verifier model, where the verifier holds a secret key, allowing the prover to generate proofs tailored to that specific verifier without revealing critical information. It adapts techniques from schemes like DV-KZG [15] to substitute pairing operations with elliptic curve scalar multiplications and largely reduces the circuit size.

GOAT BitVM2 aims to enable a trust-minimized Bitcoin zkRollup based on the BitVM2 protocol and Garbled Circuit. Its core innovations include: 1) introducing a chain based synchronization primitive over BitVM2 for operators to share collateral in multiples reimbursements; 2) combining Atomic Swap with BitVM2 to implement a user-friendly Bridge-in and Bridge-out UX (see Section 3.2 for more details); 3) introduction of universal operator abstraction and shifting the collateral inside BitVM2 from L1 to L2 to establish a concise and efficient penalty and incentive mechanism; and 4) integration of GCs with DV-SNARK to optimize verification efficiency.

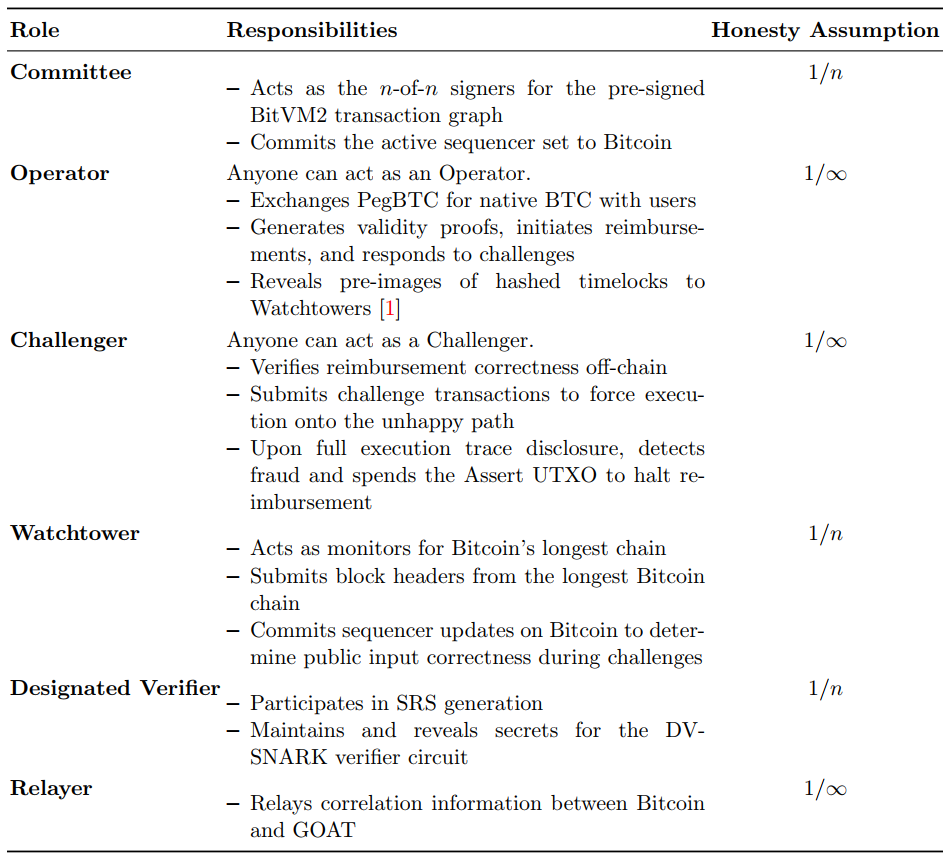

In this section, we introduce the main roles and components of GOAT BitVM2 in relation to the overall Rollup protocol.

The key participants in the GOAT BitVM2 protocol consist of the Committee, Operator, Challenger, Watchtower, Designated Verifier, and Relayer. Their primary duties are defined as follows in Table 1 and the protocol consolidates all system roles (Prover, Challenger, Sequencer, and Designated Verifier) into a single Operator identity, which we call Universal Operator. Universal Operators stake tokens on L2 and are assigned different roles in rotating epochs. It achieves certain key advantages:

In summary, this design unifies different functions into a single pool of staked Operators who share and rotate all responsibilities, mitigating centralization risks, and supporting a sustainable incentive mechanism.

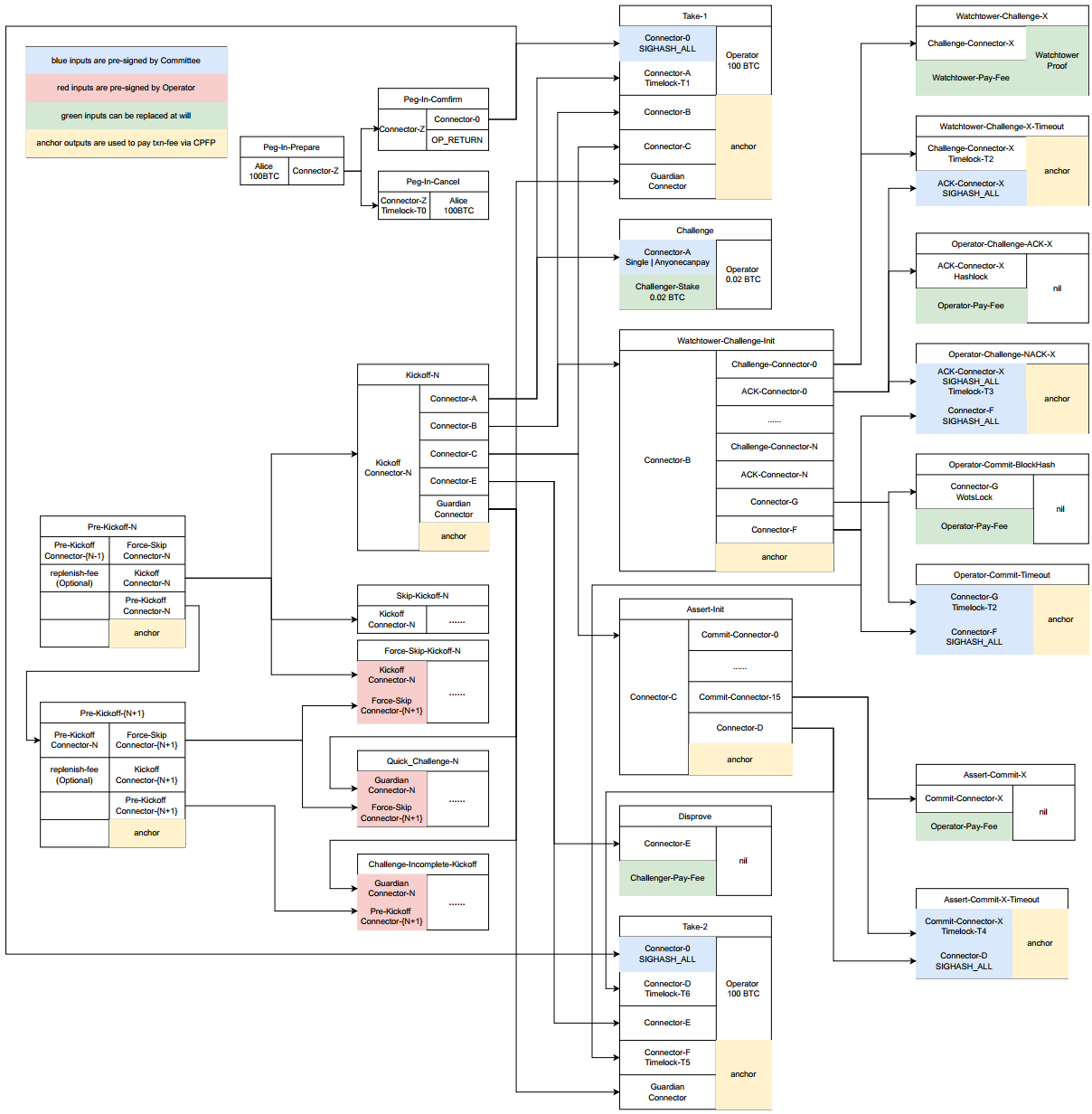

As illustrated in Fig. 3, we introduce the lifecycle of the bridge protocol between Bitcoin mainnet (L1) and GOAT Network (L2), and demonstrate the deposit and withdrawal with user Alice.

Peg-In-Prepare: User Alice locks 100 BTC in a specific output to initiate the deposit process.Peg-In-Confirm: Confirms the deposit operation. Subsequently, Alice receives 100 PegBTC on the L2 chain.Peg-In-Cancel: A fallback path. Alice can refund her BTC if the ‘Peg-In-Conform‘ transaction is not confirmed in ‘T0‘, when the timelock expires. Here, we modify the BitVM2 protocol in two important ways, 1) integrating the Watchtower mechanism, and using Watchtowers to monitor Bitcoin’s longest chain; 2) shift the collateral of the operator and challenger to the L2, making it work with Atomic Swap, and incidentally ensuring that the verifier who initializes the ‘Challenge‘ transaction is rewarded the bonus - even if another verifier submits a successful ‘Disprove‘ transaction. Based on this fair incentive mechanism, CPFP is used for operators and verifiers to pay the transaction fee on different exit paths.

Pre-Kickoff and Kickoff transactions on Bitcoin. These transactions contain the Operator’s commitment of the L2’s state root.Kickoff transaction, a challenge period begins, in which challengers first submit a Challenge transaction to end the operator’s exit from Take1, and then submit the fraud proof to disprove the withdrawal. A special type of challenger, namely Watchtower, should submit their Bitcoin longest chain with block number, including the sequencer set commitment of L2’s consensus system, and also the corresponding state root.Take1 transaction, receiving 100 BTC.Challenge transaction).Watchtower-Challenge-Init transaction and initialize a HTLC with each watchtower. This implies that the operator allocates each watchtower a hash lock - but keeps the pre-image at the beginning - then waits for the watchtowers to submit their witness transaction (Watchtower-Challenge). At least one watchtower submits it’s own Bitcoin longest header chain in this transaction by a Groth16 proof in our security setting. After a timeout T4, the operator has to acknowledge the watchtower’s witness by revealing the pre-image in timeout T5.Assert-Init and Assert-Commit) transaction to prove its correctness.Take2. If no challenger submits Disprove, the operator can proceed with the withdrawal using Take2.Optimizing the Transaction Graph As shown in Fig. 3, GOAT BitVM2 focuses on three pivotal upgrades designed explicitly to enhance the Transaction Graph’s performance and reliability:

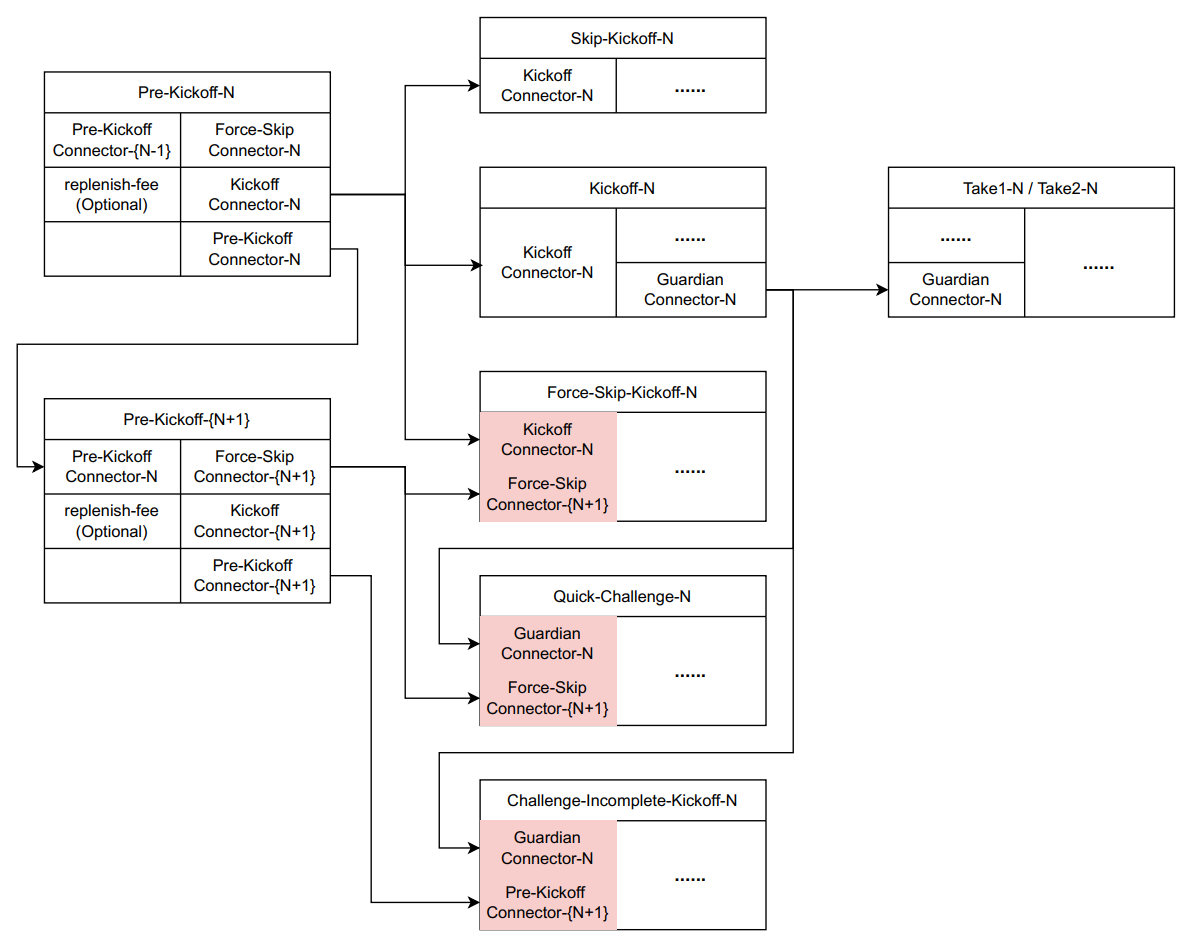

Peg-out requests sequentially. As outlined in Fig. 4, For operator, 1) if the Operator completes reimbursement in Graph-N, or actively skips it, they can directly enter the next Graph (i.e., broadcast Pre-Kickoff-N+1). If, upon entering the (N+1)th Graph, the Nth Kickoff has been broadcast but reimbursement is not completed, the challenger can issue a challenge via Challenger-Incomplete-Kickoff, which will result in the Operator’s Graphs after N+1 all becoming unavailable. If, upon entering the (N+1)th Graph, the Nth Kickoff or SkipKickoff has not yet been broadcast, the challenger can issue a challenge via Force-Skip-Kickoff, which will result in the Operator’s Nth Graph becoming unavailable.

In the original BitVM2 protocol, the operator locks it’s collateral on L1 directly and leverages an experimental opcode OP BLOCKHASH to check its confirmation in the longest chain, but this is not operational. Instead, GOAT BitVM2 requires the operators to lock collateral on L2, and use the Atomic Swap to pay the end-user. In this way, we can simplify the original protocol.

The Operator locking contract serves as a prerequisite for network participation and duty fulfillment, such as handling Peg-in/Peg-out operations and generating proofs. Its core objectives include providing security assurances and enabling permission authentication. The locking mechanism consists of two essential steps - facilitating the secure transition of funds from an unrestricted state to one governed by the protocol.

Based on the locking contract, the committee member can verify the operator’s qualification to act as a valid operator for the user’s Peg-in and have enough funds to kick off the withdrawal.

To unlock the funds from the locking contract, the operator must:

Take1/Take2 transactions have been fully processed or discarded.PreKickoff-connector output via a Non-PreKickoff transaction, demonstrating that no further Kickoff transactions canbe initiated.The slashing mechanism is the core defense against malicious operator behavior. System security is not based on trusting the Operator’s honesty but on a crypto-economic game theory mechanism. By making the economic cost of malicious behavior far exceed any potential gain, the slashing mechanism fundamentally discourages the Operator from acting maliciously. We need to state that as long as one Operator acts honestly, any malicious conduct by the remaining Operators will not result in loss of user assets.

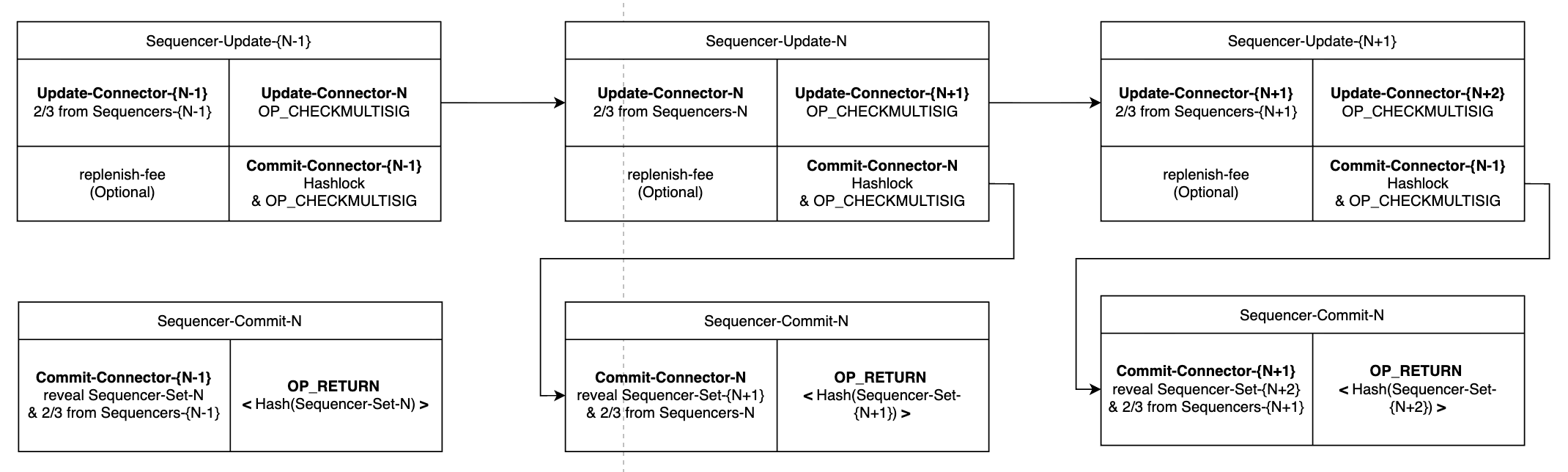

GOAT BitVM2 runs on a decentralized sequencer network to resist liveness attacks, and publish the sequencers’ public key on Bitcoin. The core idea is to use a chain of pre-signed Bitcoin transactions to ensure that any change to the L2 Sequencer set is approved by a sufficient number (e.g., 2/3) of the current members and anchored on the Bitcoin.

The commitment of the sequencer set’s public key needs a trusted setup ceremony and then the publishing of the new set once it is updated in the sequencer network by opening the old commitment via Bitcoin threshold signature in Fig. 5.

The core of the update process revolves around two key transactions: the Sequencer-Update transaction, which primarily triggers and organizes the update process, and the Sequencer-Commit transaction, which carries the hash commitment of the next cycle’s (N+1) Sequencer set, signed by a majority of the sequencers.

When the sequencer set is changed in round N, all sequencers use the Update-Connector-N as the first input of the transaction Sequencer-Update-N and commit the new sequence set’s hash in the transaction Sequencer-Commit-N. Specifically:

Sequencer-Update-N and Sequencer-Commit-N transactions are fixed, except for the UTXO used to supplement fees and the fee rate setting, which require consensus among nodes.Commit-Connector includes a hash lock for the next round’s sequencer set. In the Validator-Commit transaction, the pre-image of the next round’s Sequencer set is revealed, and an OP_RETURN output is used to commit to the hash of the next round’s Sequencer set for easier verification.After collecting signatures from 2/3 of the Sequencers for both Sequencer-Update-N and Sequencer-Commit-N transactions, they are broadcast on the Bitcoin network, finalizing the sequencer set update.

The L2 Bridge contracts consist of a PegBTC, a CommitteeManagement, and a Gateway. PegBTC refers to Wrapped BTC, a tokenized version of Bitcoin’s native cryptocurrency, BTC. PegBTC is pegged 1:1 to the value of BTC and complies with the ERC-20 token standard.

The CommitteeManagement contract is a multisig contract to manage the committee member’s registration, rotation, and exit, leveraging the decentralized sequencer network to achieve the agreement.

The Gateway contract acts as the bridge to work with BitVM2 pre-signed transactions to implement the core rollup.

Init-Withdraw: An operator initiates the withdrawal process by calling this function. Itlocks the user’s PegBTC tokens and the corresponding Peg-in record on the L2, preventing double-spending.Proceed-Withdraw: After the initiation, this function is used to submit the final withdrawal transaction, leading to the burning of the PegBTC tokens on the L2. Disprove-Withdraw: triggers a successful L1 challenge, confiscates the operator’s collateral,and rewards the challenger.Finish-Withdraw: this function is called to finalize the process once the operator’s reimbursement is successful. The BitVM2 protocol is widely used to build bridge protocols with certain advantages:

These designs ensure that funds are secured by the cryptographic guarantees of the smart contract itself, rather than by a traditional, centralized third party.

BitVM2 enables the creation of covenants on Bitcoin, which involves planning and securing a set of Bitcoin transactions before any funds are moved. The detailed steps are:

The protocol combines the following:

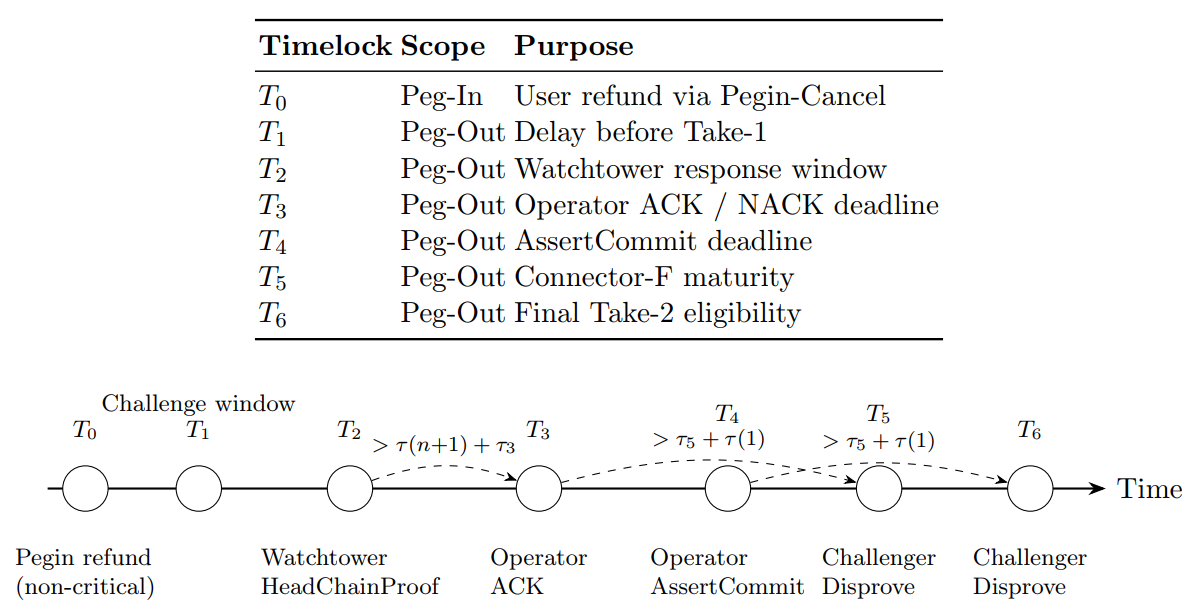

Timelocks and Global Timing Model The protocol relies on Bitcoin timelocks to enforce safetyand dispute resolution.

Key Properties

Deposit Protocol Flow

Deposit State Machine

\[\text{Init} \xrightarrow{\text{Prepare}} \text{Prepared} \xrightarrow{\text{Confirm}} \text{Completed}\]

Refund path:

\[\text{Prepared} \xrightarrow{\frac{\text{Cancel}}{T_0}} \text{Refunded}\]

Invalid behavior results in the Discarded state.

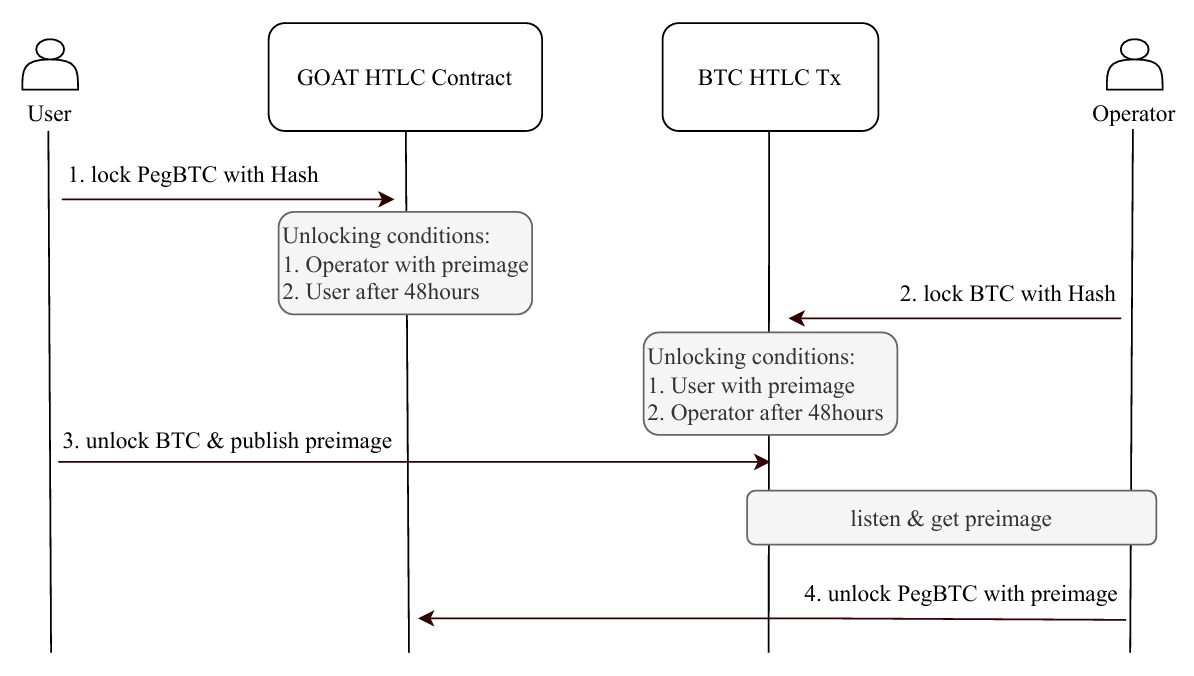

Withdrawal Protocol Flow. The withdrawal protocol enables a user to redeem PegBTC on Layer 2 for native BTC on the Bitcoin blockchain. The protocol is realized via a cross-chain atomic swap, combining a hash time-locked contract (HTLC) on Layer 2 with a corresponding HTLC transaction on Bitcoin. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the user first locks PegBTC on Layer 2 using a hash commitment, while the operator subsequently locks BTC on Bitcoin with the same hash. The user redeems BTC by revealing the preimage on Bitcoin, which is then observed by the operator to unlock PegBTC on Layer 2. Timeout conditions on both chains ensure atomicity and protect both parties against counterparty failure. A basic atomic swap requires the user to manage the preimage explicitly, which may lead toa suboptimal user experience. This requirement can be eliminated by incorporating Bitcoin SPV verification, allowing the Layer 2 system to learn the preimage trustlessly without introducing additional security assumptions.

The Peg-Out is the procedure for the operator’s funds to exit from L2 to L1, and involves the following steps:

Peg-Out State Machine We can abstract the Peg-Out protocol into the following simplified state machine:

\[\text{Idle} \xrightarrow{\text{Init-Withdraw}} \text{Kickoff}\]

\[\text{Kickoff} \xrightarrow{\text{No Challenge}} \text{Take-1/Take-2} \rightarrow \text{Finalized}\]

\[\text{Kickoff} \xrightarrow{\text{Challenge}} \text{Watchtower-Monitoring}\]

\[\text{Watchtower-Monitoring} \xrightarrow{\text{Watchtower Proof}} \text{Operator-Response}\]

\[\text{Operator-Response} \xrightarrow{\text{ACK / AssertCommit}} \text{Verification} \quad , \quad \text{Operator-Response} \xrightarrow{\text{NACK / Timeout}} \text{Slashed}\]

\[\text{Verification} \xrightarrow{\text{No Dispute}} \text{Take-2 / Finalized} \quad , \quad \text{Verification} \xrightarrow{\text{Disprove}} \text{Slashed}\]

This state machine emphasizes the main stages:

This abstraction hides lower-level transaction details (e.g., CPFP, Anchor outputs, Connector-F)while retaining the essential economic and security guarantees.

This protocol demonstrates that a trust-minimized Bitcoin–Layer2 bridge can be constructed using multisignature Committees, transaction graphs, and optimistic dispute resolution, while preserving strong economic incentives and cryptographic verifiability.

To ensure that an Operator can legitimately withdraw funds from the Bitcoin network (i.e., initiate a Peg-out), the Operator must prove two critical facts on the L2 chain: 1) that they possess and have burned the corresponding assets, and 2) that this burning operation is included in the correct, canonical L2 state. The validity of this L2 state itself is derived from the most recent Sequencer set commitment, which must be proven to have been legitimately updated and recorded on the Bitcoin blockchain. The workflow for generating the definitive Operator Proof, which guarantees the legitimacy of a Peg-out, relies on the sequential verification of four core components:

By chaining these proofs together, the system constructs an irrefutable cryptographic guarantee that the Operator is using the correct and agreed-upon L2 state for the Peg-out. Any attempt to use an invalid or forked state will fail the verification process, allowing a Challenger to detect the fraud, submit a dispute, and trigger a slashing penalty, thereby securing the system against malicious withdrawal attempts.

A data availability (DA) layer for zkRollups must satisfy the following properties: (i) mandatory publication of all state-transition data, (ii) public retrievability by any verifier, and (iii) consensus level enforcement such that missing data invalidates the corresponding state update. Bitcoin fails to meet these requirements due to the absence of a programmable, stateful execution layer and native mechanisms for enforcing data publication.

Although arbitrary data can be embedded in Bitcoin transactions (e.g., via OP_RETURN or witness data), Bitcoin provides no means to reject state transitions when such data is unavailable. Bitcoin consensus validates only transaction correctness and proof-of-work, but does not verify data completeness or retrievability. Consequently, a zk proof may attest to the correctness of a rollup state19transition even when the underlying data is unavailable, placing data availability strictly outside Bitcoin’s consensus scope. Therefore, Bitcoin-based zkRollups must rely on external DA layers or adopt validity-only (validium-style) trust assumptions.

On GOAT Network, a set of decentralized sequencers forms a permissionless execution layer, where each sequencer maintains a full replica of the Rollup state and collectively guarantees system liveness. All Layer 2 state transitions are recorded in an L2 State Chain, whose virtual blocks encode incremental state differences. These state differences are accumulated until reaching a pre-definedsize threshold, after which they are published to the Bitcoin blockchain as data commitments. Using the Watchtower mechanism in conjunction with Bitcoin header chain proofs, the system verifies that the data publication transaction has been confirmed on Bitcoin, thereby providing a verifiable and censorship-resistant record of Layer 2 state evolution.

Garbeled Circuits (GC) enables an Evaluator to perform computations on encrypted data (known as labels), with visibility restricted solely to the inputs supplied by the Garbler and the resulting labels of intermediate and final values. This cryptographic primitive facilitates verifiable computation on the Bitcoin network. In the proposed design, the Operator (acting as the Garbler) constructs a GC that represents a ZKP verifier circuit. The Operator commits to a set of all possible input and output labels. During the verification phase, if a proof is invalid, revealing the corresponding labels results in a 0-output label. This specific value can then be used on-chain to Disprove the malicious Operator’s claim and trigger a penalty.

By streamlining the Disprove process, this approach significantly reduces the complexity of the dispute procedure and its on-chain cost, making BitVM2 practically feasible.

The integration of a Designated Verifier substantially reduces the complexity of the underlying verification circuit, resulting in a GC that is more efficient to construct and verify.

The integration of GC into the BitVM2 framework primarily involves three phases: Peg-in,Assert, and Disprove. The latter two phases are activated during the Peg-out process when a challenge is presented.

The detailed workflow is structured as follows:

Kick-off.The architectural shift necessitates substantial engineering changes in both on-chain and off-chain components to support the GC-based paradigm:

OP_SHA256 to validate that the submitted GC data matches the committed hash.To ensure security, the protocol requires at least one honest Designated Verifier. During the Peg-in setup, n (i.e., 10) verifiers are selected, and the GC’s are produced in n independent copies.

The system guarantees that if at least one of the verifiers is honest and performs correctly, it can prevent a malicious Operator from successfully executing an illegal BTC withdrawal.

The DV-SNARK-based BitVM2 scheme significantly reduces the size of GC and decreases off-chaincommunication overhead. When instantiated with the pairing-friendly BN254 curve, the GC size can be reduced by approximately five times. In contrast, using the Sect233k1 curve—which does not natively support efficient pairings—can achieve a reduction of about two orders of magnitude, compressing the GC from hundreds of gigabytes to just a few gigabytes compared to traditional SNARKs that rely on pairing verification.

For the BN254 curve, the pairing property can be leveraged to directly verify the correctness of the SRS [6]. However, using Sect233k1 introduces new challenges for SRS verification, as alternative methods—such as interactive proofs or circuit-based checks—must be employed in the absence of efficient pairings.

SRS Correctness Burden for Sect233k1. Each Designated Verifier must generate an individual SRS (no universal reference string exists), requiring rigorous validation. When using non-pairing friendly elliptic curves such as Sect233k1, verifying SRS correctness becomes computationally intensive - often exceeding the cost of GC verification itself when using methods like non-interactive zero-knowledge (NIZK) proofs.

Combining Cut & Choose and Randomized Challenge Solution. Instead of direct SRS verification, the protocol employs a probabilistic game to ensure SRS reliability under Sect233k1 using parameters (n,m,k):

With parameters n = 20, m = 2, and k = 10, the probability of an honest Porver fails to pass the DV-SNARK verification circuit in face of a malicious Verifier is bounded by:

\[\frac{2}{n(n-1)} \cdot (1-\alpha)^n \alpha^2 \leq \frac{1}{190} \cdot \left(\frac{10}{11}\right)^{20} \cdot \left(\frac{1}{11}\right)^2 \approx 6.5 \times 10^{-6}\]

The cryptographic parameters for BitVM2 with DV-SNARK are configured as follows:

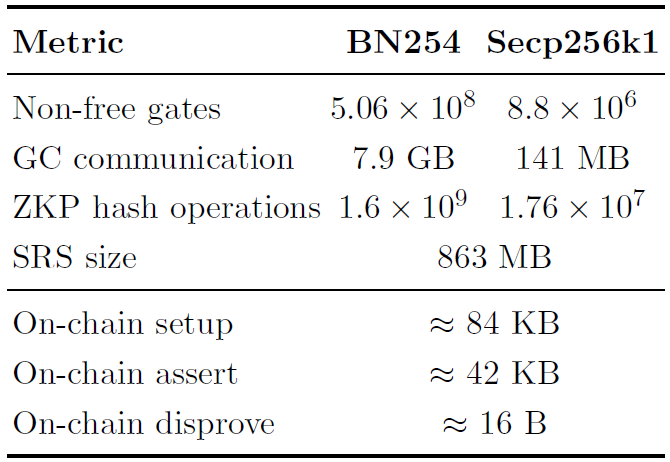

Complexity Analysis The DV-SNARK verifier circuit based on the Secp256k1 curve comprisesapproximately 8.8 million non-free gates. Our analysis considers a single garbled circuit (GC); in practice, n distinct GC circuits are required for n verifiers.

On-chain Complexity. The total size of on-chain inputs is 268 bytes, including the SNARK proof, public inputs, and trapdoor values. We employ Lamport signatures with a 160-bit hash output to commit to all input bits and the output bit. For each bit, two 128-bit labels are generated as secret keys.

The resulting on-chain communication overhead consists of: (i) a setup phase for committing to all input bits, (ii) an assert phase revealing one label per input bit, and (iii) a disprove phase revealing only the output label. The concrete costs are summarized in Table 2.

Off-chain Complexity. Off-chain costs include both communication and computation overheads arising from garbled circuit transmission, structured reference string (SRS) distribution, and zeroknowledge proof generation. A detailed comparison between BN254 and Secp256k1 is also shown in Table 2.

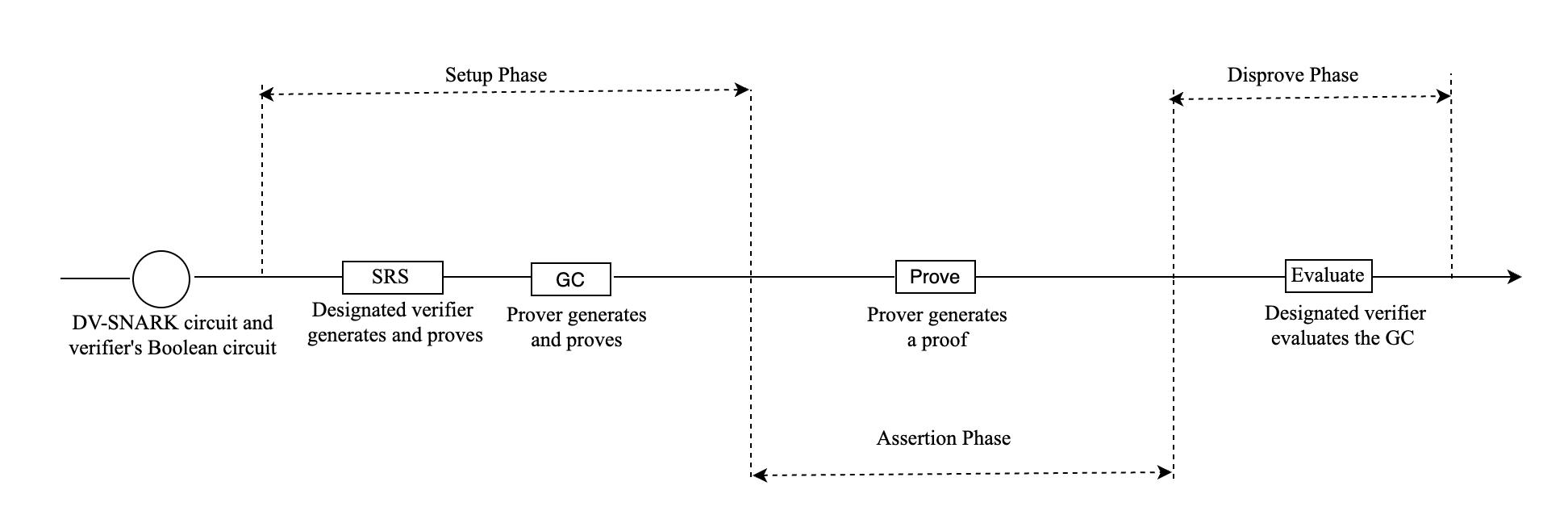

The primary computations within the process are concentrated in the Bridge-In phase. The Assertion in the Reimbursement Process only involves a proving for the DV-SNARK circuit, and the Disprove in the Reimbursement Process only requires evaluating the GC. The key computational steps are illustrated in the Fig. 7 .

The process begins with a DV-SNARK circuit (designed for verifying off-chain computations) and a verifier’s Boolean circuit. First, the designated verifier generates the SRS and must subsequently prove its correctness or ensure its validity via a specific protocol. Then, the prover constructs the GC and must prove the correctness of the GC.

During the Assertion phase, the prover generates a proof and discloses the input labels corresponding to both the proof and the trapdoor (later revealed by the Designated verifier). If the proof is invalid, the designated verifier (or any other Challenger) can initiate a Disprove by evaluatingthe GC circuit.

The measured execution times for these major computational steps are summarized in the accompanying hackmd doc. With the exception of the GC proving step, all other processes can becompleted quickly (within minutes) on a 16-core AMD EPYC 7R13 processor. The computationally intensive GC proving is accelerated by 8 NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs. The total number of Boolean gates is 2.0/2.4 billions, with 506/8.8 millions non-free (AND) gates for BN254/Sect233k1, and The GC is transformed into about 344/66 billion cycles respectively. Currently, with an 8-GPU configuration, the Ziren system can prove approximately 24 million cycles per second. This performance translates to a total GC proof generation time of about 4 hours for the BN254 curve and a much faster 0.8 hours for the Sect233k1 curve, demonstrating significant potential for real-world deployment. Furthermore, since we can partition the total circuit into smaller independent sub-circuits, the entire proving process can be substantially accelerated through parallel sub-circuit execution with additional GPU scaling.

GOAT BitVM2 significantly advances practical zkRollups on Bitcoin by systematically extending the canonical BitVM2 protocol.

First, GOAT BitVM2 generalizes the original BitVM2 construction for building native Bitcoin zkRollups. This extension integrates an Atomic Swap that supports arbitrary withdrawal amounts, together with a chain-based synchronization primitive that enables Rollup operators to share collateral across multiple reimbursements in a secure and capital-efficient manner.

Second, building upon the extended BitVM2 protocol, GOAT BitVM2 introduces on-chain consensus layer verification using a watchtower mechanism and a decentralized sequencer architecture, materially enhancing the Rollup’s liveness and decentralization. Furthermore, the Universal Operator Abstraction formalizes the allocation of revenue and risk among the participating roles, thereby synergistically incentivizing broader participation by challengers and strengthening the overall security of the network.

Third, the GOAT BitVM2 implementation demonstrates significant performance improvements that effectively bridge the gap between theoretical design and practical application. By integrating with the Ziren proof system, Operator reimbursement proofs can now be generated in approximately 40 seconds - a substantial reduction that makes frequent on-chain verification feasible. Furthermore, current GC proof generation times (4 hours for the SRS verification-friendly curve BN254 and 0.8 hours for curve Sect233k1 using a composed verification method) demonstrate the practical viability of our approach.

GOAT BitVM2 establishes a solid foundation for the continued evolution of Bitcoin Layer-2 solutions. Future work will focus on strengthening the robustness and formal verification of the optimistic computation model, optimizing SNARK verifier’s Garbled Circuit[4] and the corresponding proof generation to achieve sub-minute latency, enabling real-time reimbursement proof generation, and substantially reducing operators’ reimbursement costs.

By demonstrating a fully functional implementation that effectively balances cryptographic security with practical performance constraints, this work contributes to the broader ecosystem of trust-minimized Bitcoin scaling solutions.